Workplace supervision for advanced practice 2025 – An integrated multi-professional approach for advanced practice development.

Updated May 2025.

Summary

This is guidance for workplace supervision of advanced practice development. It is for supervisors, employers, those driving workforce development, and educators.

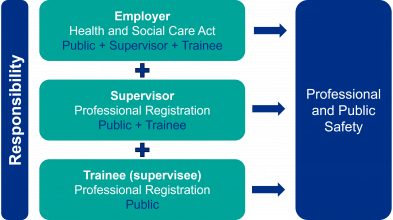

High-quality workplace supervision is crucial for both professional and public safety. It is an integral part of healthcare for all levels of practice and supports continuous professional learning across the healthcare workforce.

There is an expectation that registered health professionals understand the purpose of and engage in supervision and continuous professional development. Employers also have responsibilities for ensuring adequate supervision and training for their employees (Health and Social Care Act 2008). The development of supervisors should be part of wider educator workforce strategy (EWS).

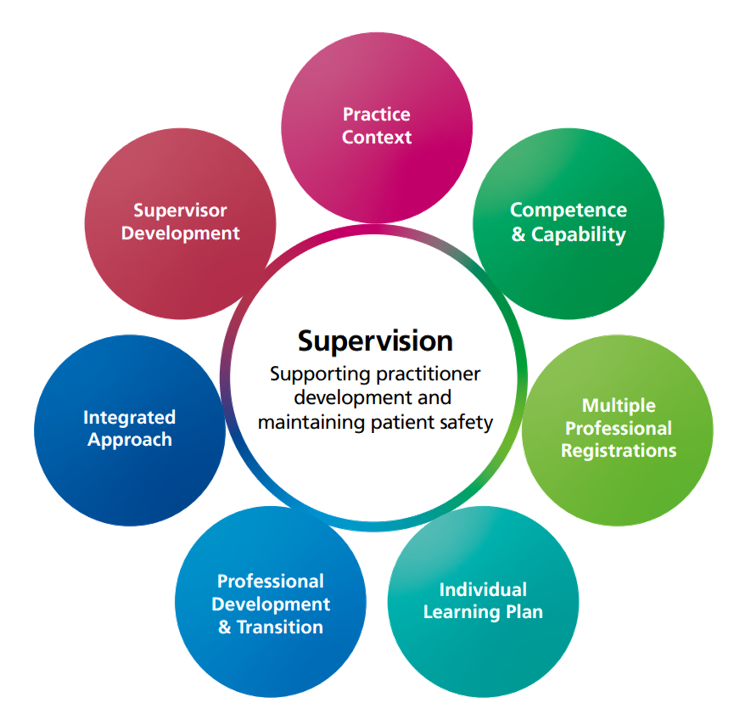

Advanced practice development requires an integrated, multi-professional approach to supervision.

There are seven fundamental considerations which underpin workplace supervision. These ensure the maintenance of both patient and professional safety during the practitioner’s advanced practice development.

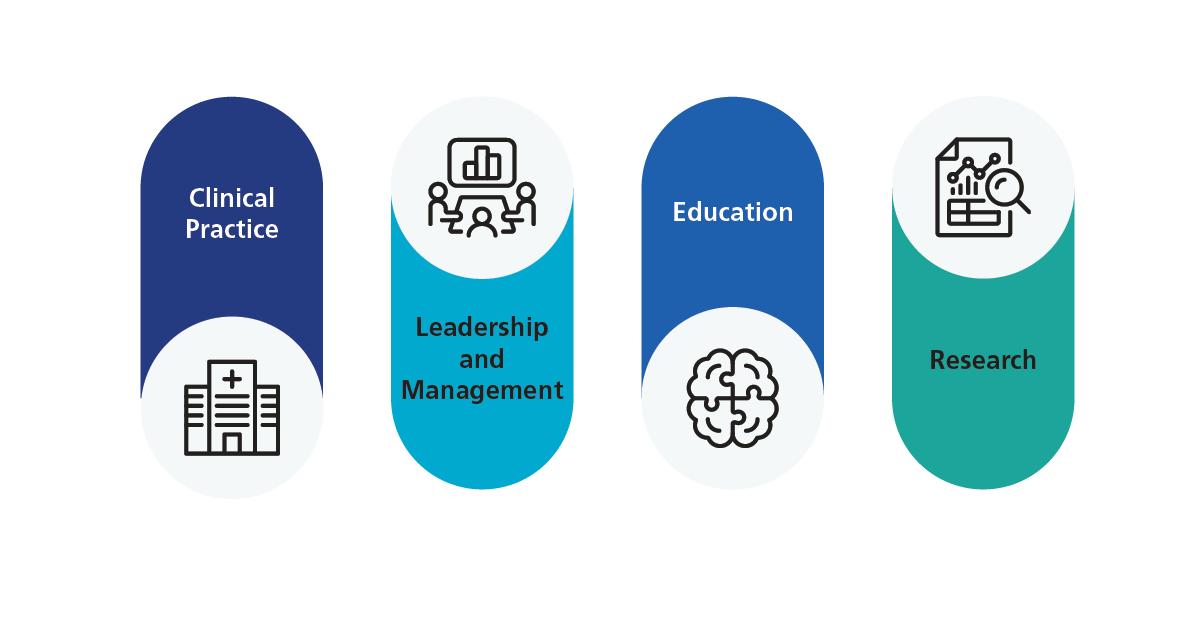

Multi-professional advanced practitioners are a growing part of the modern healthcare workforce. NHS health and care policy recognises their valuable contribution to patient care and pathways (NHS 2023). Advanced practice consists of registrants from a range of professional backgrounds who have advanced level capabilities across the four pillars. As illustrated in Figure 2.

The Multi-professional Framework for advanced practice in England sets out these capabilities.

Development in advanced practice usually combines practice-based (workplace) learning and training with academic learning at level 7 (master’s). Delivery is often through a traditional higher education institution (HEI) programme or via an integrated degree apprenticeship.

The practitioner progressing to advanced level practice requires workplace supervision which is responsive to individual learning and development needs. Each developing advanced practitioner should have a nominated ‘Coordinating Education Supervisor’ to support them throughout the period of development. They should also have access to a variety of ‘Associate Workplace Supervisors’. Associate supervisors are matched to specific learning or developmental needs across the four pillars of advanced practice.

Non-urgent advice: Employers should ensure that:

- appropriate supervision arrangements are in place

- supervisors have access to learning and development opportunities, enabling them to provide effective supervision

- advanced practice workforce and business planning includes the identifiable provision of supervision

- advanced practice workforce and business planning includes identifiable investment in supervisor development

Non-urgent advice: Do not assume that in advanced practice:

- existing uni-professional workplace supervision practices will map neatly to the learning needs of multi-professional advanced practitioners

- that uni-professional colleagues have shared understanding of the professional scope or typical clinical practice profile of developing advanced practitioners from different qualifying professions

This is a rapidly developing field of multi-professional practice across a growing range of settings. There may be differences in supervision arrangements associated with geography, pathways, practice context and roles. Variation from the Centre for Advancing Practice Minimum Standards for Supervision should be justified, agreed and documented locally.

Non-urgent advice: This guidance exists because:

Contents

Embedding the fundamentals of advanced practice supervision in practice can be daunting and may raise concerns about resourcing. The guidance has a separate section for each fundamental consideration with links to relevant resources.

1. The practice context

The drivers that prompt the development of advanced practice roles vary from service to service.

Designing workplace supervision for the developing advanced practitioner begins with a focus on the advanced practice demands.

It is important to identify what the practitioner needs to be competent and capable to assess, treat and manage at an advanced level.

Core advanced practice capabilities are set out in the Multi-professional Framework for advanced practice. Additional capabilities may be relevant in some clinical settings and specialties (see section 2 and Credentials).

The focus should be on advanced level capabilities rather than professions. This ensures that the expertise and added value of professions less traditionally associated with a specified practice setting are not overlooked.

Existing job descriptions for uni-professional roles in the specified setting may provide a helpful starting point. However, these should be used with caution and carefully reviewed. Advanced practitioners are not substitutes for more familiar professionals. Advanced practitioners are experienced, registered professionals from a variety of professional backgrounds trained to an advanced level.

The advanced practice demands for some roles are already well-established. These are some recognised specialty curricula:

- Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM)

- Faculty for Intensive Care (FICM)

- Centre for Advancing Practice endorsed credential specifications

Development of further area specific curricula and capability frameworks continues (see section 2).

When establishing advanced practice for the first time, identifying and agreeing the practice demands is a crucial first step. It is then possible to agree the competences and capabilities which the developing practitioner is working towards. In turn, this guides how best to supervise the different aspects of learning and development. This workplace supervision is vital for professional and public safety.

There will be overlap between advanced practice and other roles. Expanding the range of registered professionals working in advanced practice adds to the effectiveness and quality of care. The advanced practice role is not a substitute for an existing, traditional, established, uni-professional role.

As registered professionals advanced practitioners work within their qualifying professional registration, to meet advanced practice demands in a specified practice setting. For some registrants, this may require meeting additional advanced practice regulatory requirements

2. Agreeing the advanced practice competence and capability

Competence in this instance refers to a consistent performance in accordance with defined standards. Capability refers to being ‘competent, and beyond this, to work effectively in situations which may be complex and require flexibility and creativity’ (Skills for Health, 2020 p9; Gardener et al, 2008).

The competences and capabilities inform the advanced practice curriculum for a specified setting. Curricula will reflect the required knowledge, skills, experiences, personal qualities, behaviours and attributes in relation to the advanced practice pillars.

An advanced practice role may share competences and capabilities with more traditional, uni-professional team roles. Uni-professional competences and capabilities are not a short-cut to the specification of advanced practice competence and capability. As highlighted in section 1, multi-professional advanced practitioners work within different qualifying professional registrations to meet advanced practice demands in a specified practice setting. Each registered profession’s scope of practice will vary; for example, prescribing may not be within scope of practice.

The Multi-professional Framework for advanced practice provides an overarching, high-level structure for curriculum development mapped to the four pillars. To address breadth of development, consider curricula in relation to the discrete pillars. In practice the pillars interweave and overlap. In some practice contexts nationally agreed clinical curricula and capability frameworks exist. For example, Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM), Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, (FICM). It is important to reach agreement about the area-specific competences/ capabilities because there will be local and speciality variation:

- in day-to-day clinical practice

- in the academic underpinning for advanced practice pillar development offered from higher education institutions/universities

Each locality and speciality must agree how to integrate academic and practice components to facilitate learning required for practitioners’ specific learning and development needs. This ensures learning, academic and workplace supervision, assessment and verification can be differentiated, co-ordinated and quality assured.

For the integrated degree apprenticeship route, academic and practice development must be mapped to the Advanced practitioner (Degree) apprenticeship standard (ST0564).

Higher education providers/universities can apply for MSc programme accreditation through the Centre for Advancing Practice programme accreditation process. Academic curricula are subject to accreditation monitoring, exception reporting and re-accreditation. Additionally, providers of integrated degree apprenticeships are subject to Ofsted inspection.

It is good practice to have regular, scheduled review of local curricula, for example when a cohort of learners complete a programme. This ensures the competences, capabilities, related curricula and supervision provision remain fit for advanced practice development in the workplace/learning environment.

2.1 Resources for advanced practice competence and capability

Speciality and area-specific curricula, competence and capability frameworks include:

- Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) Emergency Care Advanced Clinical Practice Curriculum

- Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, (FICM) Advanced Critical Care Practitioner Programme

- The Ophthalmic Common Clinical Competency Framework – Curriculum (OCCCF)

- Musculoskeletal Core Competency Framework

- Core Capabilities Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice (Nurses) Working in General Practice / Primary Care in England

Nationally, work continues to agree multi-professional area specific capabilities and curricula guidance for advanced practice in different care settings.

3. Understanding multi-professional registrations and scope of practice

The multi-professional nature of the advanced practice workforce differentiates it from other health and care provision by registered professionals. This has implications for recruitment into advanced practice development/trainee posts and the accompanying education and practice- based workplace supervision because:

- developing practitioners will have different professional starting points reflecting different professional registrations, prior practice and supervision experience; nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals (AHPs)1 and so on

- developing practitioners are experienced registrants with a recommended minimum of three years post registration practice experience

- there is no single underpinning, pre-registration professional training for practitioners developing to an advanced practice level. This is in contrast to the way that practitioners such as nurses or doctors, though ultimately specialising, share common pre-registration foundations for their respective professions

- the scope of practice for different registered professions varies; for example, not all professional registrations extend to independent or supplementary prescribing2

- advanced practice workplace supervisors and those they supervise may hold different registrations. No assumptions can be made that their experiences, beliefs and expectations about supervision are the same

The training and development of advanced practice workplace supervisors should address:

- familiarisation with professional registrations

- professional scope of practice

- the implications for advanced practice

Familiarity with the developing practitioner’s qualifying registration and scope of practice underpins:

- expectations about the developing advanced practitioner’s pre-existing clinical knowledge and skills

- the learning and development which will support the practitioner to augment existing knowledge, skills, experiences, behaviours and characteristics to an advanced practice level

- the design, provision and delivery of workplace supervisory practices to ensure practitioner and public safety during advanced practice development and beyond into ongoing practice

3.1 Resources to support understanding of multi- professional registrations and scope of practice

The professional regulators/registration bodies for professions working in advanced practice roles in the NHS in England are:

- Nursing and Midwifery Council, (NMC)

- Health and Care Professions Council, (HCPC)

- General Pharmaceutical Council, (GPhC)

For further discussion of the development of supervisors for multi-professional advanced practice see section 7.

4. Developing and agreeing an individual learning plan

Developing an individual learning plan (sometimes called a personal development plan), begins with an appraisal of the professional’s learning needs. This provides a mechanism to document:

- each practitioner’s existing professional knowledge, skills, experiences, behaviours, and characteristics

- each practitioner’s development plan. Agreeing which aspects of the existing knowledge, skills, experiences, behaviours and characteristics will need additional development in practice and off-the-job, to ensure competent, capable, safe and effective advanced practice

- a baseline against which to track and record development in the specified capabilities, and competences for the target advanced practice role

- the added value different professional registrations bring to the practice setting for patient benefit

How far a practitioner is from the advanced practice level will vary from professional to professional. This reflects the combination of professional registration, pre-registration curriculum and subsequent practice-acquired knowledge, skills, experiences and post-registration training/qualifications. With a range of highly experienced registered professionals developing in advanced practice, an appraisal of learning needs helps to identify where and in what ways the practitioner is at, or close to, the advanced practice level. The practitioner and supervisor can then identify where the developing practitioner has more significant learning, development and supervision needs and/or priorities across the four pillars.

The appraisal of individual learning needs informs the development of an bespoke learning plan which states:

- which aspects of the practitioner’s development are workplace or practice-based and which are off-the job

- which aspects of off-the-job development are met through academic learning at level 7 (masters) and which higher education provision has been identified and agreed

- how workplace/practice-based and off-the- job development will be coordinated to ensure new knowledge and skills are applied safely, competently and capably in the relevant practice context

The individual learning plan should include agreement about:

- the workplace supervision arrangements for the developing practitioner, ensuring supervision matches specific areas of advanced practice development, (see section 6)

- access to practice-based development which is not available in the developing practitioner’s workplace (where identified as a learning need)

- arrangements for assessment and verification of workplace/practice-based development and required competences/capabilities (see section 2), including the identification of suitable assessors

In a given workplace/practice setting, a consistent approach should be adopted for both learning needs analysis and the individual learning plan; using consistent documentation and templates. For advanced practice degree apprentices, an initial learning needs analysis (INLA) is obligatory to ascertain which academic modules of learning are required.

A learning development plan should include a range of workplace learning and development activities which might include Direct Observation of Practical Skills (DOPS), Case based Discussion (CbD), Observed Clinical Event (OCE), Supervised Learning Event (SLE), Clinical Evaluation Exercise (CEX) and so on. These approaches are well-established in some professional groups and less so in others. It cannot be assumed that the developing advanced practitioner already familiar with these learning or assessment formats.

Discussing and agreeing the learning development plan provides an opportunity to:

- explore possible learning activities which are relevant for the identified development

- agree who is best placed to provide supervision

4.1 Resources to support individual learning planning

Some settings may already have an established learning needs analysis approach. Processes, such as Person Development Plans (PDP) may be relevant, but only following a review. The approach adopted should have a good fit across the pillars of practice with multi-professional development considerations such as cross-profession supervision and verification.

5. Professional development and transition

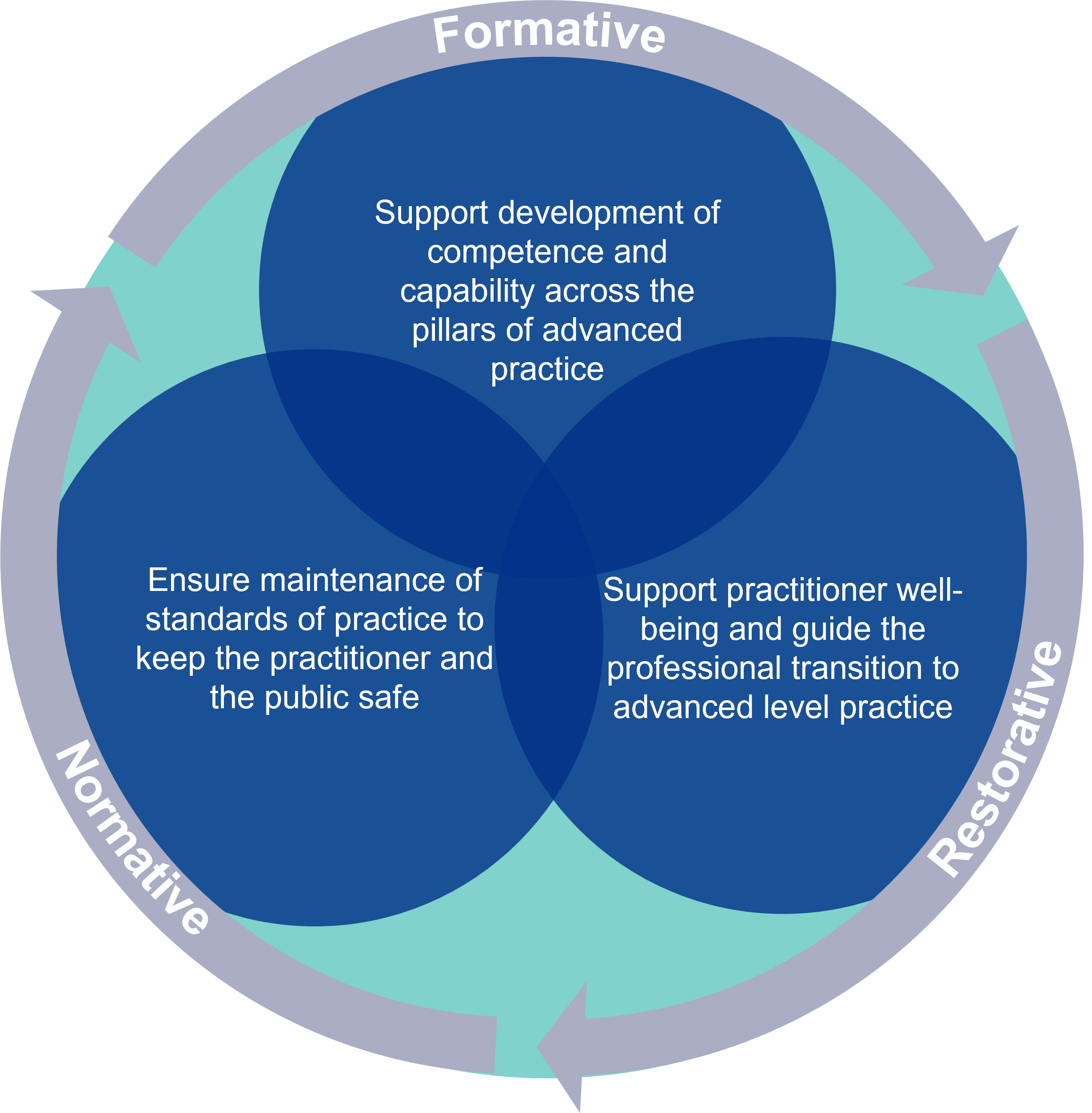

Supervision in healthcare is often framed through three overlapping dimensions, as outlined by Proctor (2008, p.7):

Formative: Supporting learning and development, knowledge and skills

Normative: Supporting maintenance of standards of practice and care

Restorative: Supporting professional well-being in practice and the impact of practice demands

Applied to the developing advanced practitioner, supervision will:

- support development of competence and capability across the pillars of advanced practice (formative)

- ensure maintenance of standards of practice to keep the practitioner and the public safe (normative)

- support practitioner well-being and guide the professional transition to advanced level practice (restorative)

It is important to schedule regular and protected time for supervision to ensure both professional and public safety. Quality not quantity of supervision will determine how effective supervision is.

Supervisors and supervisees should discuss and agree the frequency and duration of supervision. These discussions should take into account:

- the demands of the practice setting

- the developing practitioner’s capability and competence

- the Centre for Advancing Practice integrated approach to supervision described in section 6

- the Centre for Advancing Practice Minimum Standards for Supervision

- factors which influence the effectiveness of supervision, (Rothwell et al 2021; Health and Care Professions Council, 2021)

5.1 Resources to support factors and issues of professional transition

Healthcare professionals are familiar with multi-professional practice settings and the contributions each profession makes to patient care. However, multi-professional advanced practice is not yet established across the whole health and care workforce. There is variation both regionally and across specialties and/or practice settings. Advanced practice roles are more developed and defined in some settings and for some professions. As a result, advanced practitioner roles are not consistently recognised and understood by fellow health professionals or by the public in the same way as traditional uni-professional roles.

Socio-professional perceptions, expectations and experiences of professional identity and the transition to a new professional role or identity are an important consideration. These considerations are not unique to advanced practice development. For example, Duchscher (2009) has described ‘Transition Shock’ experienced by newly qualified nurses. Similar challenges are recognised in advanced practice (Moran and Nairn, 2017; Murphy and Mortimore, 2020).

Socio-professional factors may have greater impact in practice settings where there is an integrated multi-professional advanced practice workforce (critical care, emergency care, surgical pathways).

Workplace supervision for the developing advanced practitioner should recognise:

- the developing advanced practitioner is already an established clinician often practising autonomously and at a high level, in a role traditionally aligned with their qualifying professional registration

- during development and beyond, advanced practitioners remain a registrant in their qualifying professional registration body, practising within the scope of the qualifying registration at an advanced level

- in a multi-professional practice context, the practitioner’s knowledge, skills, experiences, behaviours and characteristics equip the advanced practitioner to meet presenting clinical and wider practice demands which are not uniquely aligned with one single professional registration

- as an emerging level of multi-professional practice, an advanced practitioner who managing practice demands usually associated with one or other registered profession may encounter some uncertainty about the role from fellow professionals and from the public

Importantly, the advanced practitioner is a registered professional managing practice demands within the scope of their own professional registration and adding value to the clinical pathway. Advanced practitioners are not a substitute for another profession.

5.2 Resources to support factors and issues of professional transition

The key resource for the support of socio- professional factors and issues of professional transition is access to supervisors who are:

- insightful about the different uni-professional starting points for developing advanced practitioners

- capable of ensuring the safe development of practitioners to advanced level across the pillars of advanced practice

- alert to the impact of socio-professional considerations

It is important that multi-professional and socio-professional considerations are explicitly discussed and explored in supervisor learning and development opportunities, as described in the Centre for Advancing Practice Supervisor Capabilities guidance.

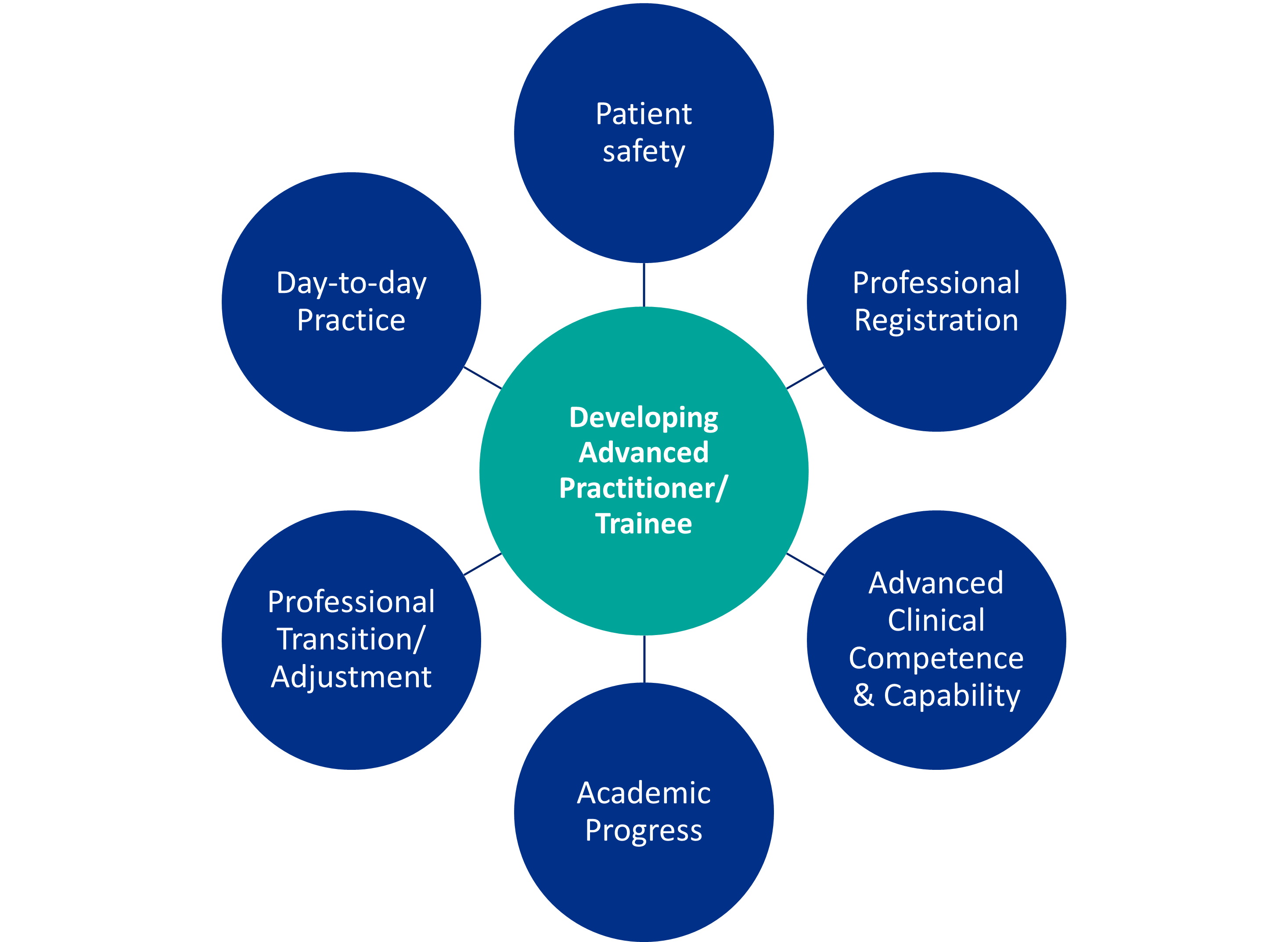

6. An integrated multi-professional approach to workplace supervision for the developing advanced practitioner

Some employers have established, designated ‘Trainee Advanced Practitioner’ roles. These roles have protected development time both in-practice (workplace) and off-the-job. Trainee advanced practice roles are not established everywhere. Developing as an advanced practitioner is demanding. It can impact both professional and personal well-being. All developing advanced practitioners balance:

- day-to-day practice demands

- the maintenance of patient safety

- their own learning, development and professional registration requirements for ongoing clinical and managerial supervision

The Centre for Advancing Practice integrated approach to workplace supervision recognises the breadth of development necessary across all four advanced practice pillars. It also ensures the developing practitioner/trainee has support with competing workplace demands and the transition to practice at advanced level.

In the workplace, a developing practitioner in advanced practice can expect to have an identified ‘Coordinating Education Supervisor.’ They should also have access to ‘Associate Workplace Supervisors’ who support specified aspects of specialty or area-specific knowledge and skills development. Associate supervision may be in relation to any of the four pillars of advanced practice.

An integrated approach with ‘Coordinating Education Supervisor’ and ‘Associate Workplace Supervisors’ is recommended because:

- the medical trainee supervision model (COPMeD, 2024) and the terminology ‘Education Supervisor’ and ‘Clinical Supervisor’ cannot be applied to all advanced practice settings

- an ‘Associate Workplace Supervisor’ may be identified to support clinical development, as with the clinical supervisor in the medical training model but equally may be identified because of their expertise in another pillar of development: education, leadership/management or research

To achieve the right match of supervisor knowledge and skills across the pillars of advanced practice, workplace supervisors will not necessarily hold the same professional registration as the developing advanced practitioner.

Identifying who already has the capabilities required in a specified practice setting can help identify individuals capable of supporting learning, development, supervision, assessment, verification and ongoing supervision. This also helps identify supervisors who will benefit from additional advanced practice supervisor development (see also section 7 and Centre for Advancing Practice Supervisor Capabilities).

The Centre for Advancing Practice provides Minimum Standards for Supervision to ensure a consistent approach to workplace supervision in advanced practice.

Further resources to support planning and implementation of supervision for advanced practice are available from the Centre for Advancing Practice:

- Minimum standards for supervision

- Employer’s advanced practice supervision action plan

- Supervisor readiness checklist

- Governance Maturity Matrix

6.1 The Co-ordinating Education Supervisor:

The Co-ordinating Education Supervisor provides a consistent supervisory relationship throughout the practitioner’s advanced practice development. They guide the practitioner’s development across the pillars of practice to an advanced practice level.

Non-urgent advice: The Co-ordinating Education Supervisor will:

- Have an in-depth understanding of the advanced practitioner’s role in the specialty, pathway or setting, including factors which may differentiate roles in advanced practice from traditional uni-professional roles in the same setting

- Have a high level of awareness of the range of potential professionals and respective scope of practice for each registration

- Understand the practice-based and off-the-job components of advanced practice development

- Support the developing practitioner with aspects of professional and role transition

- Support the developing practitioner to balance competing workplace and development demands as an employed registered professional

- Signpost to more specialist professional or personal support when indicated

- Have completed professional development which includes a focus on multi-professional supervision and practice-based education (see section 7 and Centre for Advancing Practice Supervisor Capabilities)

- Guide and signpost the developing practitioner to identify Associate Workplace Supervisors capable of supporting specialty, pathway or setting-specific knowledge and skills

- Ensure access to sufficient, structured, practice-based learning opportunities to ensure the practitioner can develop the agreed advanced practice competences and capabilities

- Ensure that a suitably authorised or approved registered professional conducts competency and capability verification or assessment

- Act as a link with the designated higher education provider/university where required for both apprentice and non-apprentice development routes

- Maintain an overview of the practitioner’s progress against an agreed individual learning plan and local/area-specific curriculum

- Maintain an overview of and address issues of professional and public safety

Development in advanced practice combines level 7 academic (master’s) learning with workplace/practice-based learning and skills’ development. Supervision for the developing advanced practitioner needs to consider the relationship between workplace coordinating education supervision and other learning, development, clinical and operational governance activities. These include:

- the relationship between advanced practice trainee supervision, assessment and verification

- the requirements for trainees who are developing as Advanced Clinical Practitioner Integrated Degree Apprentices (Degree Apprenticeship Standard: ST0564)

- any pathway specific standards, competences or capabilities required for the advanced practitioner’s role

- the place and role of identified associate workplace supervision for advanced practice specific skills development

- the place for pastoral support

- supporting a transition from a traditional uni-professional to an advanced practice professional identity

6.2 Associate Workplace Supervisors:

Associate Workplace Supervisors are practice-based practitioners who are experienced in practice-based education and the supervision of experienced registered professionals. The developing advanced practitioner can expect to work with a variety of associate workplace supervisors. Each will be matched to support the development of specific, identified aspects of advanced practice capability and/or competence. An associate workplace supervisor should be appraised of the multi-professional considerations associated with advanced practice development and supervision.

Non-urgent advice: Associate Workplace Supervisors will:

- Work collaboratively with the coordinating education supervisor and the developing practitioner to support a specified aspect of advanced practice development in a specialty, pathway or setting

- Have an in depth understanding of the supervised aspect (clinical, education, leadership/management or research) of advanced practice in relation to the practitioner’s specified advanced practice role

- Guide the practitioner’s development in the specified aspect of advanced practice from uni-professional to a multi-professional advanced practice level

- Have an awareness of the range of potential professionals and scope of registration for those developing in the advanced practice setting

- Have completed professional development with a focus on supervision and practice-based education (see section 7and Centre for Advancing Practice Supervisor Capabilities)

6.3 Employer responsibility

Advanced practice development takes place in a live and dynamic clinical context. There are multiple stakeholders in terms of clinical, operational and education governance. Each stakeholder’s immediate governance focus may differ. However, the overarching aim is to support practitioner development while simultaneously ensuring safe and effective care.

Recommendations following Kirkup (2015) have prompted a policy shift regarding supervision practices which separates regulatory aspects of supervision from professional development aspects. This transferred the responsibility for workplace supervision from statute to employer.

The provision of workplace supervision for advanced practice development should be integrated into the local workforce strategy. This should recognise the need for investment in coordinating education supervisor and associate workplace supervisor capacity, capability and competence (see section 7 and Centre for Advancing Practice Supervisor Capabilities).

Where advanced practice workforce development is via the Advanced Clinical Practitioner Integrated Degree Apprenticeship, there are specified contractual requirements which employers must fulfil, (Institute forApprentices and Technical Education, 2018).

Health and care professionals engage in career-long learning and development. In advanced practice development, employers will need to ensure the balance between employee and learner demands. Job plans offer one approach for agreement, documentation and monitoring.

6.4 Barriers and facilitators of effective supervision

Supervision practices are widely supported and endorsed throughout health and care policy and by the professional regulators. However, there are also acknowledged organisational and personal barriers to supervision (Bush, 2005).

Organisational barriers include:

- the resourcing of workplace supervision

- productivity challenges associated with supervision as a non-patient-facing activity

- the availability and prioritisation of training for supervisors

Personal barriers include:

- perceptions that supervision is not relevant

- dissatisfaction with the supervision available

- mistrust of the purpose of structured supervision and associated reflective practice

Non-urgent advice: Organisational barriers include:

- the resourcing of workplace supervision

- productivity challenges associated with supervision as a non-patient-facing activity

- the availability and prioritisation of training for supervisors

Non-urgent advice: Personal barriers include:

- perceptions that supervision is not relevant

- dissatisfaction with the supervision available

- mistrust of the purpose of structured supervision and associated reflective practice

Resources: overcoming commonly encountered supervision barriers and/or supervision more satisfactorily facilitated.

6.5 Resources to support the development of an integrated approach to supervision for the developing advanced practitioner

Adopting approaches developed for a uni-professional context cannot be assumed to be best-fit for multi-professional advanced practice. A framework or approach designed for a specified profession should not be adopted for use in multi-professional advanced practice without due critical considerations of the strengths and limitations of the approach in the multi-professional context. Appraisal of current supervisor resources and training may be necessary, to encompass advanced level practice. This can build on prior multi-professional developments and reduce duplication.

While advanced practitioners are not substitute doctors, there are contexts where there is overlap between medical trainee roles and those of advanced practitioners. Where this is the case, the approach to advanced practice development has drawn on the medical model set out in ‘The Gold Guide’, the reference guide for postgraduate medical specialty training (COPMeD, 2024).

Other supervision guidance documents from the United Kingdom include:

- The characteristics of effective clinical and peer supervision in the workplace: a rapid evidence review

- NHS Employers Supervision Resources

- The Safe Learning Environment Charter

- Supervision guidance for primary care network multidisciplinary teams

- A-Equip: a model of clinical midwifery supervision

- Professional nurse advocate A-EQUIP model

- Enhancing supervision for postgraduate doctors in training

- Clinical supervision: A framework for UK Ambulance Services

7. Developing and supporting multi-professional advanced practice workplace supervisors

Supervisor training should prepare workplace supervisors fully to recognise and support the differentiating factors of advanced practice. The Centre for Advancing Practice Guiding Principles for Supervisor Learning and Development sets out:

- ten dimensions of capability for Coordinating Education Supervisors and Associate Workplace Supervisors

- indicative supervisor development

- guidance for maintaining supervisor capability

There are numerous resources, courses and programmes which aim to develop registered professionals as workplace, practice-based educators, supervisors and assessors. Many will not have been developed to reflect the advanced practice context. As indicated in section 6, appraisal of current supervisor training may be required, to encompass advanced level practice.

A proportionate approach to training and development for the two different workplace supervisor roles is encouraged. Associate workplace supervisors will require an awareness of the differentiating factors for the developing advanced practitioner but arguably not in the same depth as a coordinating education supervisor.

Those with overall responsibility for workplace supervision of advanced practice development will need to agree the extent of augmented training, which is relevant for associate workplace supervisors, commensurate with the scope of the associate’s supervisory responsibilities and the professional registration of those whose development is being supervised.

7.1 Additional resources supervisor development and ongoing support

Royal College of Emergency Medicine Advanced Clinical Practice Supervisor Training

Blogs and free supervision resources, including a practitioner permeability check list

Continued support for the advanced practitioner

This guide sets out what should be in place for the workplace supervision of registered health professionals developing in advanced practice. As with any registered health and care professional, once the practitioner’s training is complete, there is a requirement for ongoing professional supervision as part of continuing professional development. The considerations about multiple professional registrations of those in advanced practice roles remain relevant for post-training advanced practice supervision.

Employers need to ensure this consideration is sustained beyond the training phase. Over time there will be increasing numbers of trained practitioners with competence and capability across the four pillars of advanced practice. Clinical, Research, Education, Leadership and Management. Each cohort of trained practitioners will add to the numbers of multi-professional advanced practice educators and supervisors who, in turn, are able to support the next generation of advanced practitioners. In the meantime, there will be a need to adapt and augment existing uni-professional approaches to meet the workplace supervision requirements necessary to meet the Long-Term Workforce Plan aspirations. Which include the continued expansion of the advanced practice workforce.

In common with other supervision guidance for the development of professional clinical practice, such as The Gold Guide (COPMeD), this guidance, ‘Workplace supervision for advanced practice: An integrated multi-professional approach for practitioner development’ will be subject to regular review, revision and reissue as part of the suite of the Centre for Advancing Practice resources and publications.

Footnotes

- NHS England recognises 14 allied health professions (AHPS): art therapists, drama therapists, dieticians, music therapists, occupational therapists, operating department practitioners, orthoptists, osteopaths, paramedics, physiotherapists, podiatrists, therapeutic and diagnostic radiographers, speech and language therapists. ↩︎

- Professional registrations which include independent or supplementary prescribing are: Nurses, Midwives, Pharmacists, Physiotherapists, Therapeutic Radiographers, Optometrists, Podiatrists; Supplementary Prescribers: Diagnostic Radiographers, Dietitians; Community Practitioner Prescribers: District Nurses and Health Visitors ↩︎